Australian Arabian Breed Standard Illustration Analysis

Reality and Artistic Impressions

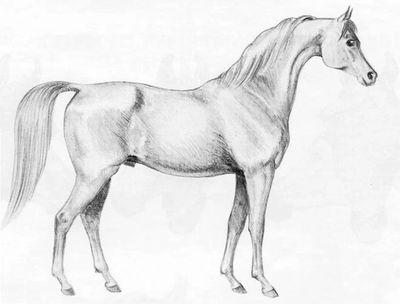

The following is an analysis of the Australia Arabian Breed Standard image, an artist's representation. This image is not a real Arabian Horse, it is an artistic view of an ideal Arabian Horse.

The analysis is using the Arabian Horse's phenotype with respect to skeletal structure. This exercise takes the reader step by step through an analytical judgement of the Arabian Horse with a view to judging, breeding, riding and driving.

It is also wise to consider that the desertbred horse was created and bred for eons on the principle that their horse who would save their lives in tribal warfare. Through cultural diversity, the desertbred horse has variety.

Note well: this artistic impression is static, joint movements are not portrayed.

Artist: Sheila Stump

All italicized text are words and phrases from Dr Deb Bennett's works: Principles of Conformation Analysis Volumes 1 - 3

For a detailed anaylsis, seek out Dr Bennett's "Conformation Insights" series as presented in EQUUS magazine - October 2009 - November 2011 and/or later updates.

The Body

The first impression is usually a lasting impression.

The viewer has an image in mind and the individual horse usually needs to fit to that ideal.

Lets look at the individual to see what it offers per the phenotype (tangible musclo-skeletal structure that in essence can be seen or palpitated).

By following the comparisons and ratios used below, an assessment can be made to see how versatile, or not, this individual maybe. Always remember, that the individual's attitude/character will carry it beyond some imperfections of its musculo-skeletal structure. Always remember: Nature compensates.

Look for overall body balance - is the body divisible by thirds?

The artistric image has a hindquarter (rear) 31.7%; trunk / body (middle) 30.9%; forehand (front) 37.4%

Governances:

Heavy chest, down-hill [forward facing back] is difficult to overcome and can predispose an individual to travelling on the forehand.

Thirds are denoted by

first third - point of shoulder, root of neck, withers and elbow.

middle third - freespan of the back

last third - point of hip, point of buttock and stifle.

The SPINE

Where is the spine - look and feel for key points where the individual's spine is.

The spine should give an indication of how the rest of the individual's bones are located, how they will attach, and perhaps function.

The spine is one continuous process, starting from the back of the skull to the very tip of the last tail bone.

The NECK

The neck's main functionality is to allow the individual to graze

Neck checks:

proportion to build

length relative to legs

length relative to body

attachment to head

placement relative to shoulder - low, medium or high

Considerations of neck lengths

Short upper curve, medium middle. long, deep lower curve

hammer headed, ewe necked, stargazer, too low root, too high head, unbalanced muscle development

Medium upper curve, medium to long middle, long, deep lower curve - common neck, less upright, maybe longer angle at throatlatch open, better than above but not as good as below

Medium to long upper curve, medium to long middle, short, shallow lower curve, straight out of front, ideal for stock work, endurance, racing, 3DE, hunter, polo

Medium to long upper curve, medium middle, short, shallow lower curve

arched neck, ideal for dressage, haute ecole, reining, park, parade, jumper

SKELETAL structure

Know where the following bones and joints (marked by circles) are:

Forehand -

- shoulder lies

- point of shoulder

- shoulder / arm joint

- arm bone

- arm / forearm joint

- forearm

- knee (forearm / cannon joint)

- cannon

- fetlock (cannon / pastern joint)

- coronet band

- hoof

Hindquarter -

- the lumbo-sacral joint (marked by oblong)

- the pelvis

- illiac / femur joint

- stifle joint (femur / gaskin)

- hock (gaskin / cannon joint)

- fetlock (cannon / pastern joint)

- coronet band

- hoof

Governances:

Where the loin meets the croup is the beginning of the lumbo-sacral joint. Lumbo-sacral joint is where the spine travels through the pelvis. This area tends to be approx 6" (size of your palm) and is the key to the hindquarter's ability. This is the top most joint and it determines the power associated with the movement. All thrust goes through the lumbo-sacral joint and then transferred to the body via the loins. Poor or weak structure in the back or lumbo-sacral joint tends to sap the energy generated by the hindquarter.

Freespan of the individual's back trades off against strength - the longer the distance between withers and coupling (lumbo-sacral joint), the weaker the individual's back

High waist (flank) as well as narrowness from nearside to offside indicates weakness, structure strain / breakdown (lumpiness).

Low stifles - the hamstring muscle ties in low which gives medium to short gaskins and low hocks.

Quadricep muscle actively bring the hindlimb forward

Long femur and short gaskin confers over-stride

Power Generator

Hindquarter pelvic length / "power generator"

Estimate, or measure where possible, the total body length and the total pelvic length. The hindquarter is the source of power which transfers through the body to make a movement happen. The pelvis is the governing structure which allows the power to generate.

Governances:

Proportion of the hindquarters compared to the overall body length

35% or more equals excellent

Between 35% and 33% equals good

Between 33% and 29% equals average

Below 29% equals poor

Overall Governing factors

Look high before looking low

- lumbo-sacral joint should be placed as far forward as possible - preferably inline with the point of hips

- croup length governs the attachment possibilities for the working muscles of the hindquarter, also acts as a fulcrum for the hindquarter muscles - conferring leverage

- all major propulsive muscles attached to the pelvis therefore the larger the pelvis, the greater the depth in pelvis provides space for the ball shaped gluteus medius muscle which initiates hind leg thrust

- femur length to iliac pelvic length determines stride length, playing a critical role in hind limb functionality

- length in the femur when compared to the gaskin equals the ability to have slow rhythm capabilities.

- always assess the hindquarter from both the side and the rear

- post-legged individuals have wide open stifles

- Since the five (5) bones that comprise the total hind limb length do not change, their total length indicates both the angulation (or not) of the hind limb and its performance ability. ...shorter and straighter (true post legged) the individual is more efficient in delivery of thrust - good for racing, draft work, jumping etc. Has low total hind limb length, wide open stifle and hock angles, tends to be flat hoofed (coon footed) - too horizontal hind pastern when weight bearing, short femur, gaskin long (compared to femur). -/- down side > stifle lock Longer, angulated hind limb easier to bring hock and hooves forward - good for dressage, reining etc. With the exception of the above short/straight hind limb - gaskin and femur should be of equal lengths -/- down side > curbs and spavins

- before assessing if an individual is post-leg or angulated, review how the individual is built at moment of thrust ie croup should be no higher than withers.

- correct angles on pasterns can negate length deficiencies

- stoutness of legs, fair length of the femur and short gaskin aids in good collection/engagement ability.

- length in leg from hip socket indicates overstride ability

- short gaskins, strong hocks has ability to 'sit'

- forward facing narrow back teamed with a set back coupling leads to stepping trot and 4-beat canter.

- well moving individual has hind joints which fold and flex elastically.

- cannons should be vertical

- ideally, stifles span a greater distance than hip sockets particularly if short coupled and round barrelled. Should display stifles that point out, hocks which point in and hooves which point out to same/similar degrees.

- closeness of hocks, cannons makes little difference as long as hocks never touch (in rest or motion), distance between hocks is relative to hip sockets

- head of femur sits obliquely in hip socket to allows stifle to point out

- look for width between stifles

- long gaskins tend to be a weakness and are indicative of cow hocks or bow legs and creates an over angulated leg (sickle hock/camped out)

- long femur and long hind cannons equates to a short gaskin (high hocks) and are indicative of a poppy action, lots of effort needed to balance movement, tends to go downhill, has trouble getting hocks underneath themselves.

- hamstring muscles should tie in low

- if the muscle cuts-in too soon, the buttocks show marked indentation.

- overdeveloped hamstring muscles hamstring muscles are doing too much work

- gluteal muscles help with thrust.

The LOIN

Loin relative to last rib denotes how tightly individuals are coupled.

Tight coupling allows for easier transference of energy (power) generated by the hindquarter to the forehand.

Short level coupling is strong can give stiff back with a better trot than canter.

Short peaked coupling isn't strong but can give a fluid canter, supple loin.

Better coupling = short which allows for elastic movement, undulating back

This image also show the depth of chest / barrel / (heart) girth relative to the length of legs.

Consider if an individual is wide (well sprung ribs) and deep through its body OR narrow - not as well sprung ribs even if otherwise deep.

HINDLEG

Alignment

When the individual is relaxed and stood square (hoof is weight bearing and cannon is vertical to the ground ie not on an angle), run a visual or imaginary plumbline down to see if the hind cannon is running true to the line and whether the cannon is parallel to the line.

STIFLE

Stifle alignment to point of hip

ideally, stifles span a greater distance than hip sockets particularly if short coupled and round barrelled. Should display stifles that point out, hocks which point in and hooves which point out to same/similar degrees.

The PELVIS

Pelvic structure and its skeletal consequences.

Pelvis: 31.7% of body length

Iliac pelvis is 72.5% of the pelvis and has an angulation of 103° to the femur.

Femur: 82.5% of the pelvis length, indicates the femur is shorter than could be expected.

Gaskin's angulation to the femur is 120°

Gaskin is longer than femur by 9% which indicates that the initial stride capability of the hindleg will be short steppening, won't overstep front hooves.

Gaskin to hind cannon is 48°

Pastern angle is indeterminable due to the set of the hindlegs

Total hindlimb length is 24% higher than the croup which makes the hindlimb well angulated ie not post legged, and also suggests that the hindlimb will force the hindquarter up when thrusting during movement.

HINDLEGs from the rear

View each leg individually

View each hindleg separately from the rear - no two legs are the same regardless if they are on the 'same end of the horse'.

Check the width of the pelvis

Bone alignments into subsequent joints - look for offset, deviation, rotation or combinations thereof.

HINDLEGs from the rear

Viewing both hindlegs together, check

View both legs and check if cannons run parallel to each other.

Assess whether the individual is base-narrow or base-wide ie where the hooves are placed relative to the width of the pelvis

Non-parallel cannons can present idiosyncrasies such as:

- vase shaped - base narrow - bow legged in movement, hoof comes in brushing cannon, carries weight on the outer edges of hooves, hocks usually bow outward

- cow hocks - stifles and hoof toe orientation don't match, bears weight on inner edges of hooves.

FOREHAND

From the side

check the lie of the shoulder

- length of arm

- length of forearm

- length of cannon

- length of pastern

- length of hooves

Check the

angle of the point of shoulder joint

angle of pastern (is it relative to the angle of the shoulder)

angle of hooves

Governances

Generally, the higher the point of shoulder and wider open the angle formed by the shoulder and the upper arm, the greater the scope and freedom of the individual's forelimb movements.

The lower the knee, the shorter the cannon bone, the stronger and more structurally stable the forelimb.

Compare pastern to cannon

too long if 75% of the cannon

too short if less than 50% of the cannon

The scapula governs entire forelimb

The humerus determines how the individual moves out front.

The humerus governs how the elbows, knee and fetlock joints fold.

The ball and socket joint of the scapula & humerus allows the only side-way movement.

longer humerus = scopey movement

shorter humerus = choppy movement

steeper rest angle of the humerus, the higher the knees can be raised

more horizontal rest angle of the humerus, less knee action and folding ability > grass clipper

should humerus actually descend straight down or even slope to the outside, abnormal movement, limb damage and unattractive conformation are the result.

upright shoulder allows -

- an individual to stand and work under themselves in the forehand if combined with a 90° angle of humerus (too horizontal),

- high knee action,

low shoulder angles strike toe first, slam heel therefore grow more toe

laid back shoulder doesn't allow exceptional jumping abilities

CHEST

Chest Box

Start with the chest box, locate the point of shoulder - remember these locations or place a dot point on the individual. Locate the point of shoulder, locate (as illustrated right) the point of elbow and transfer that location to the front of the chest. Connect these four points by drawing a box (illustrated middle). The box with indicate

depth of the chest

balance of the chest

how the legs will 'fall' from the chest (body) of the horse

FOREHAND front

Skeletal alignments

As like the rear - review the front legs separately.

Check alignment of all bone structures. Does each bone exit from the each joint in a balanced manner down to the very last bone in the hoof.

Can you see an offset, a deviation and/or rotation in these bones relative to the chest, in one or both leg(s)? What can be seen in one leg, may not be seen in the other. Review each leg separately.

Middle image - can you see the offside front leg is expressing deviation into the knee and a deviation out of the knee. The lines into and out of the circles / joints are not straight. The hoof is showing a tendency to rotate out and yet, places the weight on the inside of the hoof allowing the outside to grow longer.

First image - the near side front leg is expressing deviation into the knee and a slight deviation out of the knee. The hoof is showing a tendency to marginally rotate out, placing the weight on the outside of the hoof allowing the inside of the hoof to grow longer.

Third image - notice that the box is not rectangular. The result is the individual is base narrow for the size of its chest. Hence the leg alignments noted above.

Governances

of the Forehand

The set of the humerus at the point of the shoulder determines the orientation of the elbow and of the lower part of the front limb. Impact:

Elbows which sit narrower than the point of shoulder lead to hooves toeing out (splayed toes). Toeing out compensates for high knees.

Elbows which sit wider than the point of shoulder lead to hooves toeing in (pigeon toed)

Toes pointing out or in are not the cause but rather the result of the structure and alignment of all the other forelimb bones.

Shield shaped knees compensate slight offset cannons.

Overall BALANCE

NECK

Check the build of the neck, relative to the build of the body such as:

feminine body - elegant neck;

masculine body - robust neck.

Review the length of the neck - can the individual reach the ground to graze without putting unnecessary strain on other parts of their body. Measure or estimate the length to the ground from mid chest as compared to the length of the underline presented by the combination of neck and head.

Review the balance of the neck to the overall body - from the mid-point of the wither is there a balance of length between the area to the rear of the mid-wither point to the area forward of the mid-wither point.

The image shows a neck length of 70.6% of leg length, therefore is shorter and will not reach the ground without this individual scissoring their front legs to eat and drink naturally.

BALANCE - body

Croup to Wither

Is the croup height relative to the wither height?

Too high in the croup - horse is down-hill or forward facing

Too low in the croup - horse is up-hill.

The croup height of this individual is relative to the wither height. Expresses a natural curve of the back.

BALANCE - body

Base of Neck to Lumbo-sacral Joint

Where is the lumbo-sacral joint relative to the root of the neck - 2 points of the spinal process?

The root of the neck is palpable, gently, with the palms of your hands and represents the last (7th) cervical vertebrae of the spine within the neck region.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.